| |

He loved the sea nymph Galateia and wooed her with song, but she spurned his advances. When he discovered her in the arms of another, Akis, he crushed the boy beneath a rock.

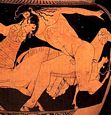

Odysseus later found himself trapped in the cave of the giant who began devouring his men. The hero plied him with wine and while he slept, pierced his eye with a burning stake. The blinded Kyklops tried to sink Odysseus' escaping ship with rocks, but failing in the attempt, prayed to his father Poseidon to avenge him.

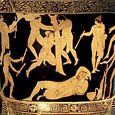

POLYPHEMUS & ODYSSEUS

Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca E7. 3 - 9 (trans. Aldrich) (Greek mythographer C2nd A.D.) :"He [Odysseus] then sailed for the land of the Kyklopes (Cyclopes), and put to shore. He left the other ships at the neighbouring island, took one in to the land of the Kyklopes, and went ashore with twelve companions. Not far from the sea was a cave, which he entered with a flask of wine given him by Maron. It was the cave of a son of Poseidon and a nymphe named Thoosa, an enormous man-eating wild man named Polyphemos (Polyphemus), who had one eye in his forehead. When they had made a fire and sacrificed some kids, they sat down to dine; but the Kyklops came, and, after driving his flock inside, he barred the entrance with a great rock. When he saw the men, he ate some.

Odysseus gave him some of Maron's wine to drink. He drank and demanded more, and after drinking that, asked Odysseus his name. When Odysseus said that he was called Nobody, the Kyklops promised that he would eat Nobody last, after the others: this was his act of friendship in return for the wine. The wine them put him to sleep.

Odysseus found a club lying in the cave, which with the help of four comrades he sharpened to a point; he then heated it in the fire and blinded the Kyklops. Polyphemos cried out for help to the neighbouring Kyklopes, who came and asked who was injuring him. When he replied ‘Nobody!’ they assumed he meant no one was hurting him, so they went away again. As the flock went out as usual to forage for food, he opened the cave and stood at the entrance with his arms spread out, and he groped at the sheep with his hands. But Odysseys bound three rams together . . . Hiding himself under the belly of the largest one, he rode out with the flock. Then he untied his comrades from the sheep, drove the flock to the ship, and as they were sailing off he shouted to the Kyklops that it was Odysseus who had escaped through his fingers.

The Kyklops had received a prophecy from a seer that he would be blinded by Odysseus, and when he now heard the name, he tore loose rocks which he hurled into the sea, just missing the ship. And from that time forward Poseidon was angry at Odysseus."

Homer, Odyssey 9. 110 ff (trans. Shewring) (Greek epic C8th B.C.) :

"[Odysseus tells the tale of his encounter with the Kyklopes (Cyclopes):] We came to the land of the Kyklopes race, arrogant lawless beings who leave their livelihoods to the deathless gods and never use their own hands to sow or plough; yet with no sowing and no ploughing, the crops all grow for them--wheat and barley and grapes that yield wine from ample clusters, swelled by the showers of Zeus. They have no assemblies to debate in, they have no ancestral ordinances; they live in arching caves on the tops of high hills, and the head of each family heeds no other, but makes his own ordinances for wife and children.

Outside the harbour of the country, neither very near it nor very far from it, there is a small well-wooded isle . . . it remains unploughed and unsown perpetually, empty of men, only a home for bleating goats. For the Kyklopes nation possess no red-prowed ships; they have no ship-wrights in their country to build sound vessels to serve their needs, to visit foreign towns and townsfolk as men elsewhere do in their voyages."

Homer, Odyssey 9.187 - 542 :

"[Odysseus tells the tale of his encounter with the Kyklopes (Cyclopes):] Then we began to turn our glances to the land of the Kyklopes tribe nearby; we could see smoke and hear voices and the bleating of sheep and goats . . . When we reached the stretch of land I spoke of--it was not far away--there on the shore beside the sea we saw a high cave overarched with bay-trees; in this flocks of sheep and goats were housed at night, and round its mouth had been made a courtyard with high walls of quarried stone and with tall pines and towering oaks. Here was the sleeping-place of a giant who used to pasture his flocks far afield, alone; it was not his way to visit the others of his tribe; he kept aloof, and his mind was set on unrighteousness. A monstrous ogre, unlike a man who had ever tasted bread, he resembled rather some shaggy peak in a mountain-range, standing out clear, away from the rest.

Most of my men I ordered to stay by the ship and guard it, but I chose out twelve, the bravest, and sallied forth . . . I had forebodings that the stranger who might face us now would wear brute strength like a garment round him, a savage whose heart had little knowledge of just laws or of ordinances.

We came to the cavern soon enough, but we did not find him there himself; he was out on his pasture-land, tending his fat sheep and goats. We went in and looked round at everything. There were flat baskets laden with cheeses; there were pens filled with lambs and kids, though these were divided among themselves--here the firstlings, then the later-born, and the youngest of all apart again. Then, too, there were well-made dairy-vessels, large and small pails, swimming with whey . . . I was eager to see the cavern's master and hoped he would offer me the gifts of a guest, though as things fell out, it was no kind host that my comrades were to meet.

Then we lit a fire, and laying hands on some of the cheeses we first offered the gods their portion, then ate our own and sat in the cavern waiting for the owner. At length he returned, guiding his flocks and carrying with him a stout bundle of dry firewood to burn at supper. This, with a crash, he threw down inside, and we in dismay shrank hastily back into a corner. Next, he drove part of his flocks inside--the milking ewes and milking goats--but left the rams and he-goats outside in the fenced yard. Then to fill the doorway he heaved up a huge heavy stone; two-and-twenty good four-wheeled wagons could not shift such a boulder from the ground, but the Kyklops did, and fitted it in its place--a massive towering piece of rock. Then he sat down and began to milk the ewes and the bleating goats, all in due order, and he put the young ones to their mothers. Half the milk he now curdled, gathered the curd and laid it in plaited baskets. The other half he left standing in the vessels, meaning to take and drink it at his supper. Having quickly despatched these tasks of his, he rekindled the fire and spied ourselves.

He asked us: ‘Strangers, who are you? What land did you sail from, over the watery paths? Are you bound on some trading errand, or are you random adventurers, roving the seas as pirates do, hazarding life and limb and bringing havoc on men of another stock?’

So he spoke, and our hearts all sank; his thundering voice and his monstrous presence cowed us. But I plucked up courage enough to answer: ‘We are Akhaians; we sailed from Troy and were bound for home . . . We have reached your presence, have come to your knees in supplication, to receive, we hope, your friendly favour, to receive perhaps some such present as custom expects from host to guest. Sir, I beg you to reverence the gods. We are suppliants, and Zeus himself is the champion of suppliants and of guests; god of guests is a name of his; guests are august, and Zeus goes with them.’

So I spoke. He answered at once and ruthlessly: ‘Stranger, you must be a fool or have come from far afield if you tell me to fear the gods or beware of them. We of the Kyklopes race care nothing for Zeus and for his aegis; we care for none of the gods in heaven, being much stronger ourselves than they are. Dread of the enmity of Zeus would never move me to spare either you or the comrades with you, if I had no mind to it myself. But tell me a thing I wish to know. When you came here, where did you moor your ship? Was it at some far point of the shore or was it near here?’

So he spoke to me, feeling his way, but I knew the world and guessed what he was about. So I countered him with crafty words: ‘My ship was shattered by Poseidon . . .’

To these words of mine the savage creature made no response he only sprang up, and stretching his hands towards my companions clutched two at once and battered them on the floor like puppies; their brains gushed out and soaked the ground. Then tearing them limb form limb he made his supper of them. He began to eat like a mountain lion, leaving nothing, devouring flesh and entrails and bones and marrow, while we in our tears and helplessness looked on at these monstrous doings and held up imploring hands to Zeus.

But when the Kyklops had filled his great belly with the human flesh that he had devoured and the raw milk he washed it down with he laid himself on the cavern floor with his limbs stretched out among his beasts. Then with courage rising I thought at first to go up to him, to draw the keen sword from my side and stab him in the chest, feeling with my hand for the spot where the midriff enfolds the liver; but second thoughts held me back, because we too should have perished irremediable; never could we with all our hands have pushed away from the lofty doorway the massy stone he had planted there. So with sighs and groans we awaited ethereal Dawn.

Dawn comes early, with rosy fingers. When she appeared, the Kyklops rekindled the fire, milked his beasts in accustomed order and put the young ones to their mothers. Having quickly despatched these tasks of his, he clutched another two of my comrades and made his breakfast of them. This over, he drove his flocks out of the cave again, easily moving the massy stone and then putting it back once more as one might put the lid back on a quiver. Whistling loud, he led off his flock to the mountain-side; so I was left there to brood mischief, wondering if I might take vengeance on him and if Athene might grant me glory.

After all my thinking, the plan that seemed best was this. Next to the sheep-pen the Kyklops had left a great cudgel of undried olive-wood, wrenched from the tree to carry with him when it was seasoned. As we looked at it, it seemed huge enough to be the mast of some great dark merchant-ship with its twenty oars . . . so long and so thick it loomed before us. I stood over this, and myself and cut off six feet of it; then I laid it in front of my companions and told them to make it smooth; smooth they made it, and again I stood over it and sharpened it to a point, then took it at once and put it in the fierce fire to harden. Then I laid it in a place of safety; there was dung in layers all down the great cave, and I hid the stake under this. I asked the men to cast lots for joining me--who would help me to lift the stake and plunge it into the giant's eye as soon as slumber stole upon him? The men that the lots fell upon were the very ones I should have chosen--four of them, and I made a fifth.

Towards nightfall the Kyklops came home again, bringing his fleecy flocks with him. He drove all the beasts into the cave forthwith, leaving none outside in the fenced courtyard--had he some foreboding, or was it a god who directed him? He lifted the massy door-stone and put it in place again; he sat down and began to milk the sheep and the bleating goats, all in accustomed order, and he put the young ones to their mothers. Having quickly despatched these tasks of his, he clutched another two of my comrades and made his meal of them. And at that I came close to the Kyklops and spoke to him, while in my hands I held up an ivy-bowl brimmed with dark wine: ‘Kyklops, look! You have had your fill of man's flesh. Now drain this bowl and judge what wine our ship had in it. I was bringing it for yourself as a libation, hoping you would take pity on me and would help to send me home. But your wild folly is past all bounds. Merciless one, who of all men in all the world will choose to visit you after this? In what you have done you defy whatever is good and right.’

Such were my words. He took my present and drank it off and was mightily pleased with wine so fragrant. Then he asked for a second bowlful of it: ‘Give me more in your courtesy and tell me your name here and now--I wish to offer you as my guest a special favour that will delight you. Earth is bounteous, and for my people too it brings forth grapes that thrive on the rain of Zeus and that make good wine, but this is distilled from nectar and ambrosia.’

So he spoke, and again I offered the glowing wine; three times I walked up to him with it; three times he witlessly drank it off. When the wine had coiled its way round his understanding, I spoke to him in meek-sounding words: ‘Kyklops, you ask what name I boast of. I will tell you, and then you must grant me as your guest the favour that you have promised me. My name is Noman; Noman is what my mother and father call me; so likewise do all my friends.’

To these words of mine the savage creature made quick response: ‘Noman that one shall come last among those I eat; his friends I will eat first; this is to be my favour to you.’

With these words he sank down on the floor, then lay on his back with his heavy neck drooping sideways, till sleep the all-conquering overcame him; wine and gobbets of human flesh gushed from his throat as he belched them forth in drunken stupor. Then I drove our stake down into the heap of embers to get red-hot; meanwhile I spoke words of courage to all my comrades, so that none of them should lose heart and shrink from the task. But when the stake, green though it was, was about to catch fire and glowed frighteningly, I drew it towards me out of the fire, while the others took their stand around me. Some god breathed high courage into us. My men took over the keen-pointed olive stake and thrust it into the giant's eye; I myself leaned heavily over from above and twirled the stake round . . . We grasped the stake with its fiery tip and whirled it round in the giant's eye. The blood came gushing out round the red-hot wood; the heat singed eyebrow and eyelid, the eyeball was burned out and the roots of the eye hissed in the fire . . . His eye hissed now with the olive-stake penetrating it. He gave a great hideous roar; the cave re-echoed, and in terror we rushed away. He pulled the blood-stained stake from his eye and with frantic arms tossed it away from him.

Then he shouted loud to he Kyklopes kinsmen who lived around him in their caverns among the windy hill-tops. Hearing his cries they hastened towards him from every quarter, stood round his cavern and asked him what ailed him: ‘Polyphemos, what dire affliction has come upon you to make you profane the night with clamour and rob us of our slumbers? Is some human creature driving away your flocks in defiance of you? Is someone threatening death to yourself by craft of by violence?’

From inside the cave the giant answered: ‘Friends, it is Noman's craft and no violence that is threatening death to me.’

Swiftly their words were borne back to him: ‘If no man is doing you violence--if you are alone--then this is a malady sent by almighty Zeus from which there is no escape; you had best say a prayer to your father, Lord Poseidon.’

With these words they left him again, while my own heart laughed within me to think how the name I gave and my ready with had snared him. Racked with anguish, lamenting loudly, the Kyklops groped for the great stone and pushed it from the door-way, then in the doorway he seated himself with outstretched hands, hoping to seize on some of us passing into the open among the sheep--so witless did he take me to be . . . There were big handsome rams there, well-fed, thick-fleeced and with dark wool. Making no noise, I began fastening them together with plaited withies, the same that the lawless monstrous ogre slept on. I took the rams three by three; each middle one carried a man, while the other two walked either side and safeguarded my companions; so there were three beats to each man. As for myself--there was one ram that was finest of all the flock; I seized his back, I curled myself up under his shaggy belly, and there I clung in the rich soft wool, face upwards, desperately holding on and on. In this dismal fashion we waited now for ethereal Dawn.

Dawn comes early, with rosy fingers. When she appeared, the rams began running out to pasture, while the unmilked ewes around the pens kept bleating with udders full to bursting. Their master, consumed with hideous pains, felt along the backs of all the rams as they stood still in front of him. The witless giant never found out that men were tied under the fleecy creatures' bellies. Last of them all came my own ram on his way out, burdened both with his own thick wool and with me the schemer. Polyphemos felt him over too and began to talk to him: ‘You that I love best, why are you last of all the flock to come out through the cavern's mouth? Never till now have you come behind the rest: before them all you have marched with stately strides ahead to crop the delicate meadow-flowers, before them all you have reached the rippling streams, before them all you have shown your will to return homewards in the evening; yet now you come last. You are grieving, surely, over your master's eye, which malicious Noman quite put out, with his evil friends, after overmastering my wits with wine; but I swear he has still not escaped destruction. If only your thoughts were like my own, if only you had the gift of words to tell me where he is hiding from my fury! Then he would be hurled to the ground and his brains dashed hither and thither across the cave; then my heart would find some relief from the tribulations he has brought me, unmanly Noman!’

So speaking, he let the ram go free outside. As for ourselves, once we had passed a little way beyond cave and courtyard, I first loosed my own hold beneath the ram, then I untied my comrades also. We herded the many sheep in haste--fat plump creatures with long shanks--and drove them on till we reached our vessel . . .

But when we were no further away [out at sea] than a man's voice, I called to the Kyklopes and taunted him: ‘Kyklops, your prisoner after all was to prove not quite defenceless--the man whose friends you devoured so brutally in your cave. No, your sins were to find you out. You felt no shame to devour your guests in your own home; hence the requital from Zeus and the other gods.’

Rage rose up in him at my words. He wrenched away the top of a towering crag and hurled it in front of our dark-prowed ship. The sea surged up as the rock fell into it; the swell from beyond came washing back at once and the wave carried the ship landwards and drove it towards the strand. But I myself seized a long pole and pushed the ship out and away again, moving my head and signing to my companions urgently to pull at their oars and escape destruction; so they threw themselves forward and rowed hard. But when we were twice as far out on the water as before, I made ready to hail the Kyklops again, though my friends around me, this side and that, used all persuasion to restrain me: ‘Headstrong man, why need you provoke this savage further? The stone he threw out to sea just now dashed the ship back to the shore again, and we thought we were dead men already. Had he heard any sound, any words from us, he would have hurled yet another jagged rock and shattered our heads and the boat's timbers, so vast his reach is.’

So they spoke, but my heart was proud and would not be gain-said; I called out again with rage still rankling: ‘Kyklops, if anyone among mortal men should ask who put out your eye in this ugly fashion, say that the one who blinded you was Odysseus the city-sacker, son of Laertes and dweller in Ithaka.’

So I spoke. He groaned aloud as he answered me: ‘Ah, it comes home to me at last, that oracle uttered long ago. We once had a prophet in our country, a truly great man called Telemos son of Eurymos, skilled in divining, living among the Kyklopes race as an aged seer. He told me all this as a thing that would later come to pass--that I was to lose my sight at the hands of one Odysseus. But I always thought that the man who came would be tall and handsome, visibly clothed with heroic strength; instead, it has been a puny and strengthless and despicable man who had taken my sight away from me after overpowering me with wine. But come, Odysseus, return to me; let me set before you the presents that befit a guest, and appeal to the mighty Earthshaker to speed you upon your way, because I am his son, and he declares himself my father. And he alone will heal me, if so he pleases--no other will, of the blessed gods or of mortal men.’

So he spoke, but I answered thus: ‘Would that I were assured as firmly that I could rob you of life and being and send you down to Hades' house as I am assured that no one shall heal that eye of yours, not the Earthshaker himself.’

So I spoke, and forthwith he prayed to Lord Poseidon, stretching out his hands to the starry sky: ‘Poseidon the raven-haired, Earth-Enfolder: if indeed I am your son, if indeed you declare yourself my father, grant that Odysseys the city-sacker may never return home again; or if he is fated to see his kith and kin and so reach his high-roofed house and his own country, let him come late and come in misery, after the loss of all his comrades, and carried upon an alien ship; and in his own house let him find mischief.’

This was his prayer, and the raven-haired god heeded it. Then the Kyklops lifted up a stone (it was much larger than the first); he whirled it and flung it, putting vast strength into the throw; the stone came down a little astern of the dark-prowed vessel, just short of the tip of the steering-oar. The sea surged up as the stone fell into it, but the wave carried the ship forward and drove it on to the shore beyond."

Homer, Odyssey 1. 68 ff :

"Poseidon the Earth-Sustainer is stubborn still in his anger against Odysseus because of his blinding of Polyphemos (Polyphemus), the Kyklops (Cyclops) whose power is greatest among the Kyklopes race and whose ancestry is more than human; his mother was the nymph Thoosa, child of Phorkys (Phorcys) the lord of the barren sea, and she lay with Poseidon within her arching caverns. Ever since that blinding Poseidon has been against Odysseus."

Homer, Odyssey 2. 19 :

"The savage Kyklops (Cyclops) had killed him [Odysseus' companion Antiphos] inside his arching cave, making a meal of him after all the rest."

Homer, Odyssey 10. 201 :

"I [Odysseus] spoke, and their [his men's] hearts quailed within them as they thought again of the deeds of Antiphates the Laistrygonian and the fierce and fearless and man-devouring Kyklops (Cyclops)."

Homer, Odyssey 10. 434 :

"The Kyklops (Cyclops) penned our companions in when they reached his steading--foolhardy Odysseus went in with them, and his presumption was their undoing."

Homer, Odyssey 13. 341 :

"[Athene appears to Odysseus on the island of the Phaiakes (Phaeacians):] ‘My heart knew well that you would return [to Ithaka], though after the loss of all your comrades, but I had no mind to challenge Poseidon, my father's brother, who had stored up rancour of heart against you because of the blinding of his son [Polyphemos].’"

Homer, Odyssey 12. 211 :

"[Odysseus to his companions:] ‘Friends, wer are not unschooled in troubles . . . [such as] when the Kyklops (Cyclops) penned us by might and main in his arching cave.’"

Homer, Odyssey 20. 17 :

"[Odysseus calms himself:] ‘Have patience, heart. Once you endured worse than this, on the day when the ruthless Kyklops (Cyclops) devoured my hardy companions; you held firm till your cunning rescued you from the cave in which you thought to die.’"

Homer, Odyssey 23. 310 :

"He [Odysseus] related [to Penelope] . . . the crimes of the Kyklops (Cyclops) and afterwards his [Odysseus'] own vengeance on him for the brave comrades pitilessly devoured."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Philoxenus of Cythera, Fragment 818 (from Synesius, Letters) (trans. Campbell, Vol. Greek Lyric V) (Greek lyric C5th to 4th B.C.) :

"Odysseus was trying to persuade Polyphemos (Polyphemus) to let him out of the cave: ‘For I am a sorcerer,’ he said, ‘and I could give you timely help in your unsuccessful marine love: I know incantations and binding charms and love spells which Galatea is unlikely to resist even for a short time. For your part, just promise to move the door--or rather this door-stone: it seems as big as a promontory to me--or I'll return more quickly than it takes to tell, after winning the girl over. Winning her over, do I say? I'll produce her here in person, made compliant by many enchantments. She'll beg and beseech you, and you will play coy and hide your true feelings. But one thing worries me in all this: I'm afraid the goat-stink of your fleecy blankets may be offensive to a girl who lives in luxury and washes many times a day. So it would be a good idea if you put everything in order and swept and washed and fumigated your room, and better still if you prepared wreaths of ivy and bindweed to garland yourself and your darling girl. Come on, why waste time? Why not put your hand to the door now?’

At this Polyphemos roared with laughter and clasped his hands, and Odysseus imagined he was beside himself with joy at the thought that he would win his darling; but instead he stroked him under the chin and said, ‘No-man, you seem to be a shrewd little fellow, a smooth businessman; start work on some elaborate scheme, however, for you won't escape from here.’

Now Odysseus, who was being genuinely wronged, was destined in the end to profit from his cleverness; whereas you, a Kyklops (Cyclops) in your boldness and a Sisyphos in your endeavours, have been overtaken by justice and imprisoned by the law--and may you never laugh at these."

Aristophanes, Plutus 299 ff (trans. O'Neill) (Greek comedy C5th to 4th B.C.) :

"We will seek you, dear Kyklops (Cyclops) [Polyphemos], bleating, and if we find you with your wallet full of fresh herbs, all disgusting in your filth, sodden with wine and sleeping in the midst of your sheep, we will seize a great flaming stake and burn out your eye."

Theocritus, Idylls 7. 158 (trans. Rist) (Greek bucolic C3rd B.C.) :

"Such nectar [wine] persuaded the shepherd beside Anapos [a Sicilian river] dance among his pens--that strong Polyphemos who pelted ships with mountains."

Lycophron, Alexandra 657 (trans. Mair) (Greek poet C3rd B.C.) :

"He [Odysseus] shall see the dwelling of the one-eyed lion [Polyphemos], offering in his hands to that flesh-eater the cup of the vine as an after-supper draught."

Quintus Smyrnaeus, Fall of Troy 8. 125 ff (trans. Way) (Greek epic C4th A.D.) :

"Antiphos [a companion of Odysseus] . . . whose doom was one day wretchedly to be devoured by the manslaying Kyklops (Cyclops) [Polyphemos]."

Philostratus, Life of Apollonius of Tyana 4. 36 (trans. Conybeare) (Greek biography C1st to C2nd A.D.) :

"It cost Odysseus to visit the Kyklops (Cyclops) in his home; though he lost many of his comrades in his anxiety to see him, and because he yielded to the temptation of beholding so cruel a monster."

Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae 1. 20a (trans. Gullick) (Greek rhetorician C2nd to C3rd A.D.) :

"The Italian Greek Oinonas was admired for his parodies of songs to the harp. He it was who introduced Kyklops (Cyclops) [Polyphemos] whistling and the stranded Odysseus talking bad Greek."

Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae 1. 10e :

"By way of denouncing drunkenness the poet [Homer] portrays the Kyklops (Cyclops) [Polyphemos], for all his great size, as completely overcome, when drunk, by a small person."

Anonymous, Odyssey Fragment (trans. Page, Vol. Select Papyri III, No. 137) (Greek epic C3rd-4th A.D.) :

"Like Antiphates and Polyphemos who devoured men."

Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 125 (trans. Grant) (Roman mythographer C2nd A.D.) :

"From there [the land of the Kikones, Cicones] he [Odysseus] went to the Cyclops Polyphemus, son of Neptunus [Poseidon], to whom a prophecy had been given by the augur Telemus, son of Eurymus, that he should beware of being blinded by Ulysses. He had one eye in the middle of his forehead, and feasted on human flesh. After he drove his flock back into the cave he would place a great stone weight at the door. He shut Ulysses and his comrades within, and started to devour the men. When Ulysses saw that he could not cope with his size and ferocity, he made him drunk with the wine he had received from Maron, and said that he was called Noman. And so, when Ulysses was burning out his eye with a glowing stake, he summoned the other Cyclopes with is cries, and called to them from the closed cave, ‘Nomas in blinding me!’ They thought he was speaking in sport, and did not heed. But Ulysses tied his comrades to the sheep and himself to the ram, and in this way they got out."

Hyginus, Fabulae 125 :

"When a raft had been made there, Calypso sent him [Odysseus] off with an abundance of provisions, but Neptunus [Poseidon] shattered the raft with his waves because he had blinded his son, the Cyclops."

Ovid, Metamorphoses 14. 160 ff (trans. Melville) (Roman epic C1st B.C. to C1st A.D.) :

"Achaemenides, abandoned long before [by Odysseus] among the rocks of Aetna . . . Achaemenides in rags no more, his clothes no longer pinned with thorns, now quite his former self, replied [to his rescuer Aeneas]: ‘May I see Polyphemus yet again, that maw aswill with human blood, if I value my home and Ithaca above this vessel here, if I revere Aeneas less than my father . . . To him I owe my life that did not end between the Cyclops' jaws, and should I leave the light of life today, a proper grave will hold me or at least not that belly! What were my feelings then (Except that terror swept away all sense and feeling) when, abandoned there, I saw you sail away to sea? I longed to shout but dreaded to betray myself; your ship Ulixes' [Odysseus'] shouting almost wrecked. I saw the Gigante wrench a huge rock from the hill and hurl it out to sea. I saw again his giant biceps like a catapult slinging enormous stones, and feared the waves or wind-whistle would overwhelm the ship, forgetting I was not aboard. But when flight rescued you from certain death, he prowled groaning all over Aetna, groping through the forest, stumbling eyeless on the rocks, stretching his bloodstained arms towards the waves, cursing the race of Greeks: "O for some chance to get Ulixes or some mate of his to vent my rage, whose guts I might devour, whose living limbs my hands might rend, whose blood might sluice my throat and mangled body writhe between my teeth! How slight, how nothing then the loss of sight they ravished!" This and more in frenzy. Horror filled me as I watched his face still soaked with slaughter, his huge hands, those savage hands, his empty sightless eye, his beard and body caked with human blood. Death was before my eyes! Yet death the least of horrors! Now he's got me, I was sure. He's going to sink my guts in his! My mind pictured the moment when I'd seen two friends time after time dashed to the ground, and he, like a hairy lion bending over them, guzzled their flesh and guts and marrow-bones, still half-alive. I shuddered as I stood blood-drained in horror, watching as he chewed the filthy feast and retched it back again, belching great bloody gobbets mixed with wine. That was the fate I fancied was in store for me, poor soul. For many days I hid, starting at every rustle, fearing death and longing too to die, my hunger kept at bay with acorns, leaves and grass.’"

Propertius, Elegies 2. 33c (trans. Goold) (Roman elegy C1st B.C.) :

"You, too, centaurus Eurytion, were undone by wine and you, too, Polyphemus, by liquor of Ismarus."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History 3. 89 (trans. Rackham) (Roman encyclopedia C1st A.D.) :

"[Near Catania in Sicily:] Then come the three Rocks of the Cyclopes, the Harbour of Ulysses."

Statius, Thebaid 6. 716 ff (trans. Mozley) (Roman epic C1st A.D.) :

"From smoke-emitting Aetna (Etna) did Polyphemus hurl the rock, though with hand untaught by vision, yet on the very track of the ship he could but hear, and close to his enemy Ulixes [Odysseus]."

Valerius Flaccus, Argonautica 4. 104 (trans. Mozley) (Roman epic C1st A.D.) :

"The wild Cyclopes in Aetna's caverns watch the straits during stormy nights, should any vessel driven by fierce south winds draw nigh, bringing thee, Polyphemus, grim fodder and wretched victims for thy feasting, so look they forth and speed every way to drag captive bodies to their king. Them doth the cruel monarch himself on the rocky verge of a sacrificial ridge, that looms above mid-sea, take and hurl down in offering to his father Neptunus [Poseidon]; but should the men be of finer build, then he bids them take arms and meet him with the gauntlets; that for the hapless men is the fairest doom of death."

|

|

|

|

|

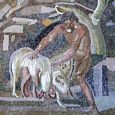

POLYPHEMUS & GALATEIA

Bacchylides, Fragment 59 (from Natale Conti, Mythology) (trans. Campbell, Vol. Greek Lyric IV) (Greek lyric C5th B.C.) :"Polyphemos (Polyphemus) is said not only to have loved Galatea but to have fathered a son Galatos on her, as Bakkhylides testified."

Philoxenus of Cythera, Fragment 817 (from Scholiast on Theocritus 6) (trans. Campbell, Vol. Greek Lyric V) (Greek lyric C5th to 4th B.C.) :

"Douris [historian C3rd B.C.] says that Polyphemos built a shrine to Galatea near Mount Aitna (Etna) in gratitude for the rich pasturage for his flocks and the abundant supply of milk, but that Philoxenos of Kythera [poet C5th B.C.] when he paid his visit and could not think of the reason for the shrine invented the tale that Polyphemos was in love with Galatea."

Philoxenus of Cythera, Fragment 818 (from Synesius, Letters) :

"Odysseus was trying to persuade Polyphemos (Polyphemus) to let him out of the cave: ‘For I am a sorcerer,’ he said, ‘and I could give you timely help in your unsuccessful marine love: I know incantations and binding charms and love spells which Galatea is unlikely to resist even for a short time. For your part, just promise to move the door--or rather this door-stone: it seems as big as a promontory to me--or I'll return more quickly than it takes to tell, after winning the girl over. Winning her over, do I say? I'll produce her here in person, made compliant by many enchantments. She’ll beg and beseech you, and you will play coy and hide your true feelings . . .’

At this Polyphemos roared with laughter . . . [and] stroked him under the chin and said, ‘No-man, you seem to be a shrewd little fellow, a smooth businessman; start work on some elaborate scheme, however, for you won't escape from here.’"

Philoxenus of Cythera, Fragment 819 (from Scholiast on Aristophanes, Plutus) :

"The tragic poet Philoxenos, who introduced Polyphemos playing the lyre . . . who wrote of the love of the Kyklps for Galatea . . . he introduces the Kyklops (Cyclops) playing the cithara and challenging Galatea . . . He says the Kyklops carries a leather bag and eats herbs."

Philoxenus of Cythera, Fragment 821 (from Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae) :

"But when the Kyklops (Cyclops) of Philoxenos of Kythera is in love with Galatea and is praising her beauty, he praises everything else about her but makes no mention of her eyes, since he has a premonition of his own blindness. He addresses her as follows: ‘Fair-faced, golden-tressed, Grace-voiced offshoot of the Erotes (Loves).’"

Philoxenos of Cythera, Fragment 822 (from Plutarch, Table-Talk) :

"Philoxenos says that the Kyklops (Cyclops) tries to cure his love with the tuneful Mousai (Muses) [i.e. with music]."

Philoxenus of Cythera, Fragment 822 (from Scholiast on Theocritus 11) :

"Philoxenos makes the Kyklops (Cyclops) console himself for his love of Galatea and tell the dolphins to report to her that he is healing his love with the Mousai (Muses) [i.e. with music]."

Philoxenus of Cythera, Fragment 823 (from Suidas) :

"‘You sacrificed: you shall be sacrificed in turn.’ The Kyklops (Cyclops) says this to Odysseus in Philoxenos."

Philoxenus of Cythera, Fragment 824 (from Zenobius, Proverbs) :

"‘With what a monster has God imprisoned me!’ The proverb is used of people who are distressed by some vexatious circumstance: the Kyklops (Cyclops) is a play by the poet Philoxenos in which Odysseus speaks the words after being shut in the Kyklops' cave."

Theocritus, Idylls 6 (trans. Rist) (Greek bucolic C3rd B.C.) :

"[The seer Telamos addresses Polyphemos:] ‘Galateia is pelting your flocks, Polyphemos, with apples, and calling you names--goatherd and laggard in love; and you, poor fool, do not see, but sit sweetly piping. Look, there again! She's hurling one at your sheepdog, and the bitch is looking out to sea and barking--you can see her silhouetted on the clear of the waves as she runs along the edge of the gently sucking sands. Watch out she doesn't rush at the child's knees, emerging from the water, and claw her fairy flesh! She's casting at you again, look--brittle as the down the torrid glare of summer leaves upon the thistle. You love, she flees; and when you leave loving, follows, staking her all upon a desperate move. Ah, Love! How often, Polyphemos, has he made unfair show fair! . . .’

[Polyphemos:] ‘I saw, yes, by Pan, I saw when she pelted the flock. It did not escape me--no, by my one sweet eye: may I see with it to the last, and may Prophet Telamos carry his hostile mouthings home, to keep for his children! But I too can use the goad, so I take no notice, and tell her I've another woman now. Apollon! Hearing that, she's all consumed with spite, and frenzied spies, form the sea, on my cave and flocks. It was I set on the dog to bark at her, too. In the days of my courting, it used to lay its muzzle against her groin and whine. When she's seen enough of this act of mine, perhaps she'll send a messenger; but I'll bar my door, until she vows in person to make my bed up fairly on this isle. Certainly I'm not ugly, as they call me; for lately I looked in the sea--there was a calm--and I though my cheeks and my one eye showed up handsome, and my teeth shone back, whiter than Parian marble. But I spat three times into my bosom, as the witch Kotytaris taught me, to turn away evil.’"

Theocritus, Idylls 11 :

"In days of old, my countryman, the Kyklops (Cyclops) Polyphemos, fared best with them, for one: he barely had a beard on lip or cheek, when he fell in love with the sea nymph Galatea. He wooed her, not with apples and roses and lovelocks, but with so fine a frenzy that all beside seemed pointless. Often enough his sheep had to find their own way home to the fold from the green pastures, while he sang of Galatea, sitting alone on the beach amid the sea wrack, languishing from daybreak, with a deadly wound which mighty Kypris [Aphrodite] dealt him with her arrow, fixing it under his heart. Nevertheless, he found the cure, and seated high on a rock, looking out to sea, this is how he would sing.

‘O white Galatea, why do you spurn my love?--whiter than curds to look on, softer than a lambkin, more skittish than a calf, tarter than the swelling grape! How do you walk this way, so soon as sweet sleep laps me, and are gone as soon, whenever sweet sleep leaves me, fleeing like a sheep when she spies the grey wolf coming! I fell in love with you, maiden, the first time you came, with my mother, eager to cull the bluebells from our hillside: I was your guide. Once seen, I could not forget you, nor to this day can I yet; not that you care: God knows you do not, not a whit!

‘O, I know, my beauty, the reason why you shun me: the shaggy eyebrow that grins across my forehead, unbroken, ear to ear; the one eye beneath; and the nose squat over my lips. For all my looks, I'd have you know, I graze a thousand sheep, and draw the best milk for myself to drink. I am never without cheeses, summer or fall: even in midwinter my cheese nets are laden. There's not another Kyklops can play the flute as I can, and I sing of you, my peach, always of me and you, till dead of night, quite often. I'm rearing eleven fawns, all with white collars, for you, and four bear cubs. come to us, then; you'll lack for nothing. Leave the green sea gulping against the dry shore. You'll do better o' nights with me, in my cave; I've laurels there, and slender cypresses; black ivy growing, and the honey-fruited vine; and the water's fresh that tree-dressed Aitna sends me, a drink divine, distilled from pure white snow. Who'd choose instead to stay in the salt sea waves? And if my looks repel you, seeming over-shaggy, I've heart of oak within, and under the ash a spark that's never out. If you will fire me, gladly will I yield my life, or my one eye, the most precious thing I have. O, why did not my mother bring me to birth with gills! Down I'd dive and kiss you hand--your lips if you'll allow--and bring you white narcissus flowers, or soft poppies, with wide, red petals--not both at the same time for one's, you see, a winter, the other a summer flower. Even so, sweetheart, I've made a start: I'm going to learn to swim, if some stranger comes this way, sailing in a ship, and find out why it is you nymphai like living in the deep. O, won't you come out, Galatea, and coming out forget, as I, as I sit here, forget to go back home!

‘You'd learn to like to shepherd sheep with me, and milk, and set the curds for cheese, dropping in sharp rennet. Only my mother does me wrong, and it's her I blame. She's never said a single word on my behalf to you, for all she sees me growing thin, day after day. I shall tell her that my head and both my feet are throbbing: so I'll be even, making her suffer, even as she makes me. Kyklops, Kyklops! Where is this mad flight taking you? You'd surely show more sense if you'd keep at your basket weaving, and go gather the olive shoots and give them to the lambs. Milk the ewe that's at hand : why chase the ram that's fleeing? Perhaps you'll find another Galatea, and more fair. Many a girlie calls me out to play with her by night, and when I do their bidding, don't they giggle gleefully! I too am clearly somebody, and noticed--on dry land!’

In this way did Polyphemos shepherd his love with song; and he found a readier cure than if he had paid hard cash."

Callimachus, Epigrams 47 (from A.P. 12.150) (trans. Trypanis) (Greek poet C3rd B.C.) :

"How excellent was the charm that Polyphemos discovered for the lover. By Gaia (Earth), the Kyklops (Cyclops) was no fool! The Mousai (Muses), O Phillippos, reduce the swollen wound of love. Surely the poet’s skill is sovereign remedy for all ill."

Philostratus the Elder, Imagines 2. 18 (trans. Fairbanks) (Greek rhetorician C3rd A.D.) :

"[Ostensibly a description of an ancient Greek painting at Neapolis (Naples):] These men harvesting the fields and gathering the grapes, my boy, neither ploughed the land nor planted the vines; but of its own accord the earth sends forth these its fruits for them; they are in truth Kyklopes (Cyclopes), for whom, I know not why, the poets will that the earth shall produce its fruits spontaneously. And the earth has also made a shepherd-folk of them by feeding the blocks, whose milk they regard as both drink and meat. They know neither assembly nor council nor yet houses, but they inhabit the clefts of the mountain.

Not to mention the others, Polyphemos son of Poseidon, the fiercest of them, lives here; he has a single eyebrow extending above his single eye and a broad nose astride his upper lip, and he feeds upon men after the manner of savage lions. But at the present time he abstains from such food that he may not appear gluttonous or disagreeable; for he loves Galateia, who is sporting here on the sea, and he watches her from the mountain-side. And though his shepherd's pipe is still under his arm and silent, yet he has a pastoral song to sing that tells how white she is and skittish and sweeter than unripe grapes, and how he is raising for Galateia fawns and bear-cubs. All this he sings beneath an evergreen oak, heeding not where his flocks are feeding nor their number nor even, any longer, where the earth is. He is painted a creature of the mountains, fearful to look at, tossing his hair, which stands erect and is as dense as the foliage of a pine tree, showing a set of jagged teeth in his voracious jaw, shaggy all over--breast and belly and limbs even to the nails. He thinks, because he is in love, that his glance is gentle, but it is wild and stealthy still, like that of wild beasts subdued under the force of necessity.

The Nymphe sports on the peaceful sea, driving a team of four dolphins yoked together and working in harmony."

Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae 1. 6e - 7a (trans. Gullick) (Greek rhetorician C2nd to C3rd A.D.) :

"[On the origin of the tale of Polyphemos and Galateia:] Phainias says that Philoxenos, the poet of Kythera [C5th B.C.] . . . was writing a poem on Galateia [the mistress of the tyrant Dionysios and her namesake Nereid] . . . . [but] when Philoxenos was detected in the act of seducing the king’s mistress Galateia, he was thrown into the quarries. There he wrote his Kyklops, telling the story of what happened to him, and representing Dionysios as Kyklops, the flute-girl as the Nymphe Galateia, and himself as Odysseus."

Aelian, Historical Miscellany 12. 44 (trans. Wilson) (Greek rhetorician C2nd to 3rd A.D.) :

"The Sicilian quarries were at Epipolai . . . The finest of the caves there was named after the poet Philoxenos, where (they say) he lived while composing the best of his poems, Kyklops, in utter disregard of the vengeance and punishment imposed by Dionysos."

Ovid, Metamorphoses 13. 728 ff (trans. Melville) (Roman epic C1st B.C. to C1st A.D.) :

"Galatea letting Scylla [before her transformation into a monster] comb her hair, heaved a deep sigh and said, ‘My dear, your suitors after all are men and not unkind: you can reject them, as you do, unscathed. But I whom sea-blue Doris bore, whose father's Nereus, who am safe besides among my school of sisters, I could not foil Cyclops' love except in bitter grief.’

Tears choked her as she told it. Scylla wiped the tears with sleek white fingers, comforting the goddess: ‘Tell me, darling. Do not hide (you know you trust me) how you were so hurt.’

And Nereis [Galateia] answered with these words: ‘Acis was son of Nympha Symaethis and Faunus [Pan] was his father, a great joy to both his parents, and a greater joy to me; for me, and me alone, he loved. He was sixteen, the down upon his cheek scarce yet a beard, and he was beautiful. He was my love, but I was Cyclops' love, who wooed me endlessly and, if you ask whether my hate for him or my love for Acis was stronger in my heart, I could not tell; for both were equal. Oh, how powerful kind Venus [Aphrodite], is thy reign!

‘That savage creature, the forest's terror, whom no wayfarer set eyes upon unscathed, who scorned the gods of great Olympos, now felt pangs of love, burnt with a mighty passion, and forgot his flocks and cares. Now lovelorn Polyphemus cared for his looks, cared earnestly to please; now with a rake he combed his matted hair, and with a sickle trimmed his shaggy beard, and studied his fierce features in a pool and practised to compose them. His wild urge to kill, his fierceness and his lust for blood ceased and in safety ships might come and go.

‘Meanwhile a famous seer had sailed to Aetna Sicula, wise Telemus Eurymides, whom no bird could delude, and warned the dreadful giant "That one eye upon your brow Ulixes soon shall take." He answered laughing "You delude yourself! Of all the stupid prophets! Someone else has taken it already." So he mocked the warning truth; then tramped along the shore with giant crushing strides or, tired anon, returned to the dark cave that was his home.

‘There juts into the sea a wedge-shaped point, washed by the ocean waves on either side. Here Cyclops climbed and at the top sat down, his sheep untended trailing after him. Before him at his feet he laid his staff, a pine, fit for the mainmast of a ship, and took his pipe, made of a hundred reeds. His pastoral whistles rang among the cliffs and over the waves; and I behind a rock, hidden and lying in my Acis' arms, heard far away these words and marked them well. "Fair Galatea, whiter than the snow, taller than alders, flowerier than the meads, brighter than crystal, livelier than a kid, sleeker than shells worn by the ceaseless waves, gladder than the winter's sun and summer's shade, nobler than apples, sweeter than ripe grapes, fairer than lofty planes, clearer than ice, softer than down of swans or creamy cheese, and, would you welcome me, more beautiful than fertile gardens watered by cool streams. Yet, Galatea, fiercer than wild bulls, harder than ancient oak, falser than waves, tougher than willow wands or branching vines, wilder than torrents, firmer than these rocks, prouder than peacocks, crueller than fire, sharper than briars, deafer than the sea, more savage than a bear guarding her cubs, more pitiless than snakes beneath the heel, and--what above all else I'd wrest from you--swifter in flight than ever hind that flees the baying hounds, yes, swifter than the wind and all the racing breezes of the sky. (Though, if you knew, you would repent your flight, condemn you coyness, strive to hold me fast.) Deep in the mountain I have hanging caves of living rock where never summer suns are felt nor winter's cold. Apples I have loading the boughs, and I have golden grapes and purple in my vineyards--all for you. Your hands shall gather luscious strawberries in woodland shade; in autumn you shall pick cherries and plums, not only dusky black, but yellow fat and waxen in the sun, and chestnuts shall be yours, if I am yours, and every tree shall bear its fruit for you. All this fine flock is mine, and many more roam in the dales or shelter in the woods or in my caves are folded; should you chance to ask how many, that I could not tell: a poor man counts his flocks. Nor need you trust my praises; here before your eyes you see their legs can scarce support the bulging udders. And I have younger stock, lambs in warm folds, and kids of equal age in other folds, and snowy milk always, some kept to drink and some the rennet curdles into cheese. No easy gifts or commonplace delights shall be your portion--does and goats and hares, a pair of doves, a gull's nest from the cliff. I found one day among the mountain peaks, for you to play with, twins so much alike you scarce could tell, cubs of a shaggy bear. I found them and I said ‘She shall have all these; I'll keep them for my mistress for her own. Now, Galatea, raise your glorious head from the blue sea; spurn not my gifts, but come! For sure I know--I have just seen--myself reflected in a pool, and what I saw was truly pleasing. See how large I am! No bigger body Juppiter [Zeus] himself can boast up in the sky--you always talk of Jove [Zeus] or someone reigning there. My ample hair o'erhangs my grave stern face and like a grove darkens my shoulders; and you must not think me ugly, that my body is so thick with prickly bristles. Trees without their leaves are ugly, and a horse is ugly too without a mane to veil its sorrel neck. Feathers clothe birds and fleeces grace the sheep: so beard and bristles best become a man. Upon my brow I have one single eye, but it is huge, like some vast shield. What then? Does not the mighty sun see from the sky all things on earth? Yet the sun's orb is one. Moreover in your sea my father [Poseidon] reigns; him I give you--my father, yours to be, would you but pity me and hear my prayer. To you alone I yield. I, who despise Jove [Zeus] and his heaven and his thunderbolt, sweet Nereis, you I fear, your anger flames more dreadful than his bolt. Oh, I could bear your scorn more patiently did you but spurn all others, but, if Cyclops you reject, why prefer Acis, Acis' arms to mine? Acis may please himself and please, alas, you Galatea. Give me but the chance, he'll find my strength no smaller than my size. I'll gouge his living guts, I'll rend his limbs and strew them in the fields and in the sea--your sea, so may he be one flesh with you! I burn! The fire you fight is fanned to flame; all Aetne's furnace in my breast I bear, and you, my Galatea, never care!"

‘Such was his vain lament; then up he rose (I saw it all) as a fierce thwarted bull roams through the woodlands and familiar fields, and, spying in his rage Acis and me, all unaware and fearing no such fate, shouted "I see you; now I shall make sure that loving fond embrace shall be your last." Loud as an angry Cyclops ought to shout he shouted; Aetna shuddered at the din. Then I in panic dived into the sea beside us; Acis had already turned his hero's back and shouted as he fled "Help, Galatea! Father, mother, help! Admit me to your kingdom for I die." Cyclops pursued and hurled a massive rock, torn from the hill, and though its merest tip reached Acis, yet it crushed and smothered him. But I (it was all fate permitted me) caused Acis to assume his ancestral powers [i.e. the youth was turned into a river-god.] . . .’

So Galatea ended and the group of Nereides dispersed and swam away across the placid waters of the bay."

Propertius, Elegies 3. 2 (trans. Goold) (Roman elegy C1st B.C.) :

"Galatea beneath savage Aetna turned her dripping horses at the sound of Polyphemus' serenade."

Valerius Flaccus, Argonautica 1. 130 (trans. Mozley) (Roman epic C1st A.D.) :

"Panope and her sister Doto and Galatea with bare shoulders, revelling in the waves, escort her [Thetis to her marriage with Peleus] towards the caverns [of Kheiron (Chiron) in Thessalia]; Cyclops from the Sicilian shore calls Galatea back."

Nonnus, Dionysiaca 6. 300 ff (trans. Rouse) (Greek epic C5th A.D.) :

"Then Pan [during the great Deluge] well soaked saw Galateia swimming under a neighbouring wavebeaten rock, and sang out: ‘Where are you going, Galateia? Have you given up sea for hills? Perhaps you are looking for the love-song Kyklops (Cyclops)? I pray you by the Paphian [Aphrodite], and by your Polyphemos--you know the weight of desire, do not hide from me if you have noticed my mountainranging Ekho swimming by the rocks! . . . Come, leave your Polyphemos, the laggard! If you like, I will lift you upon my own back and save you. The roaring flood does not overwhelm me; if I like I can mount to the starry sky on my goatish feet!’

He spoke, and Galateia said in reply: ‘My dear Pan, carry your own Ekho through the waves--she knows nothing of the sea. Don’t waste your time in asking me why I am going here this day. I have another and higher voyage which Rainy Zeus and found me. Let be the song of Kyklops, though it is sweet. I seek no more the Sikelian (Sicilian) Sea; I am terrified at this tremendous flood, and I care nothing for Polyphemos.’"

Nonnus, Dionysiaca 14. 52 ff :

"One alone was left behind from the war [when the rest of the Kyklopes were summoned by Rheia to join Dionysos in his war against the Indians], Polyphemos, tall as the clouds, so mighty and so great, the Earthshaker's [Poseidon's] own son; he was kept in his place by another love, dearer than war, under the watery ways, for he had seen Galateia half-hidden, and made the neighbouring sea resound as he poured out his love for a maiden in the wooing tones of his pipes."

Suidas s.v. Threttanelo (trans. Suda On Line) (Byzantine Greek Lexicon C10th A.D.) :

"Philoxenus the dithyramb poet or tragedian wrote The Love of the Kyklops for Galateia; and then that he said the word threttanelo in the epigram in imitation of a sound of the cithara. For there he brings on the Kyklops playing the cithara and making Galatea blush."

- Homer, The Odyssey - Greek Epic C8th B.C.

- Greek Lyric IV Bacchylides, Fragments - Greek Lyric C5th B.C.

- Greek Lyric V Philoxenus, Fragments - Greek Lyric C5th B.C.

- Apollodorus, The Library - Greek Mythography C2nd A.D.

- Aristophanes, Plutus - Greek Comedy C5th-4th B.C.

- Theocritus Idylls - Greek Idyllic C3rd B.C.

- Callimachus, Fragments - Greek Poetry C3rd B.C.

- Lycophron, Alexandra - Greek Poetry C3rd B.C.

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, Fall of Troy - Greek Epic C4th A.D.

- Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae - Greek Cullinary Guide C3rd A.D.

- Aelian, Historical Miscellany - Greek Rhetoric C2nd-3rd A.D.

- Philostratus the Elder, Imagines - Greek Rhetoric C3rd A.D.

- Greek Papyri III Anonymous, Odyssey Fragments - Greek Elegiac C3rd-4th A.D.

- Hyginus, Fabulae - Latin Mythography C2nd A.D.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses - Latin Epic C1st B.C. - C1st A.D.

- Propertius, Elegies - Latin Elegy C1st B.C.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History - Latin Encyclopedia C1st A.D.

- Valerius Flaccus, The Argonautica - Latin Epic C1st A.D.

- Statius, Thebaid - Latin Epic C1st A.D.

- Nonnos, Dionysiaca - Greek Epic C5th A.D.

- Suidas - Byzantine Greek Lexicon C10th A.D.

0 comments:

Post a Comment